A question that has been lingering. It’s fair game, but before I get around to actually answering, let’s remember how we got here.

Late 90’s

Before the first open source iam product existed we had standard policy enforcement protocols in use. Examples include Java’s ee security & jaas. Unix had PAM, sudo and kerberos. Windows, NTLM and SPNEGO. There were web-based protocols like HTTP basic auth and ISAPI.

IAM Complete Solution Defined

Those policy enforcement mechanisms didn’t meet the wider requirements of a complete solution:

- extensible and pluggable policy enforcement services

- centralized policy decision point services

- common policy administration services

- common policy information services

- audit and review capabilities

The gaps made us scramble to meet the need.

Early to Mid 2000’s

Commercial vendors ruled. Several more policy enforcement protocols appeared including liberty, saml, ws-*, xmlsecurity and xacml. Those in need either built or bought because open source iam solutions were barely in existence.

There were many open source projects that provided the legos to build with.

2008

The era of opportunity for open source innovation. Most of the technical problems were solved. All one had to do was assemble a solution using the building blocks available in the public domain.

But not another access control framework. Needed a complete solution.

2009

As code construction commenced on fortress, many open source policy enforcement frameworks became widely used, such as spring security and opensso, but still no complete solution.

2011

Around the the time of the first fortress release the situation changed. Sun’s merger with Oracle foretold the end of the commercial vendor stranglehold creating a void in which companies like Symas, Linagora, Evolveum, and Tirasa sprung complete solutions.

Today

Now that we have several complete open source iam solutions on the market, the industry continues to focus on policy enforcement standards, the latest being oauth, uma and open id connect.

But we continue to struggle because uniform policy enforcement is the tip of iceberg. More benefit comes through shared policy decision and admin services. This promotes reuse of infrastructure and data across organizational, vendor and platform boundaries.

Tomorrow

Policy enforcement protocols will continue to be volatile and ill-equipped.

Standards-based policy decision and admin services will continue to be needed.

So that Vendor A’s PEP can plug into Vendor B’s PDP, and Vendor C’s PAP can plug in Vendor D’s PIP.

Why Fortress

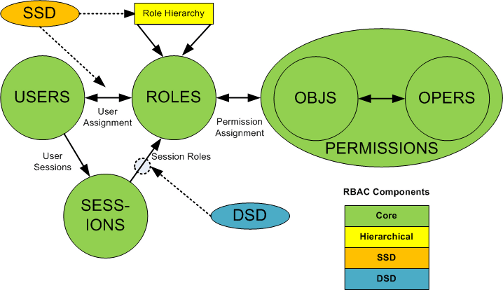

Based on ansi incits 359, our best hope for standardizing the complete iam solution.